2012 was an important year in music history: it was Claude Debussy’s 150th birthday. Debussy is one of the most important and innovative composers of all time. He was born just outside Paris on 22 August 1862 and studied piano at the Paris Conservatoire. But he excelled at composition and won a coveted Prix de Rome in 1884. On returning to Paris, Debussy spent the next fifteen years establishing himself as a free-lance composer. Success finally came in 1902 with the premier of Pelléas et Mélisande; he was subsequently accepted the Légion d’honneur, an exclusive publishing contract, and a position on the advisory board of the Paris Conservatoire. Debussy spent his latter years in a state of depression, grappling with ill health, marital troubles, financial difficulties, and doubts about his creative powers. He died at home in Paris on 25 March 1918.

During his illustrious career, Debussy wrote music of every type: songs, piano pieces, chamber music, operas, ballets, and symphonic works. These works have influenced musicians of every stripe: from classical musicians to jazzers, rockers, and rappers. Piano players will know “Clair de lune,” a short salon piece that he wrote around 1890. Film junkies will remember hearing a dance mix of “Clair de lune” in Ocean’s Eleven (2001) when Julia Roberts and George Clooney get the hots for each other. The tune also appears in the soundtracks to countless other films including Frenchman’s Creek (1944), (1948), Frankie and Johnny (1991), and Twilight (2008).

But Debussy is famous for other reasons. One is that he believed in the basic affinity between the arts. This idea was one that was promoted by Charles Baudelaire in his poem “Correspondances” (Les Fleurs du mal) to explain how it is possible to recall a given event, location, or person synaesthetically by perceiving certain colors, sounds, smells, or sensations. For his part, Debussy cultivated this idea in pieces inspired by Baudelaire: for example, the title of the piano prelude “Les Sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir” actually comes from “Harmonie du soir,” another poem from Les Fleurs du mal. Debussy also liked to collaborate with Symbolist/Impressionist writers and painters on multi-media projects. The opera Pelléas et Mélisande is a good case in point: Debussy worked closely with the playwright Maurice Maeterlinck, at least up until the final stages of production.

Another way in which Debussy left his mark on music was by expanding the scope of classical music to encompass other types of music, especially popular music. Once again, he endorsed views that were originally championed by Symbolist/Impressionist writers and painters. In his essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” Baudelaire focused not on the work of a traditional painter, but on that of Constantin Guys, a commercial artist who created pictures for theIllustrated London News. Debussy followed suit: he was fascinated by music of the street, of the circus, of cafés, of marching bands, and even of the early cinema. His encounters with the famous clowns Footit and Chocolat inspired him to compose cakewalks for piano, such as “Minstrels” and “Général Lavine—eccentric.” For Debussy, the crucial difference was not between classical and popular music, but between good and bad music.

Debussy also had a habit for recycling particular pieces in several different guises. This idea is one that also resonates with Symbolist/Impressionist aesthetics, especially Monet’s concept of the series painting. Starting in the late 1880s, Monet created strings of paintings that represent a single motif under different atmospheric conditions: these include series devoted to haystacks, (1891), the façade of Rouen Cathedral (1894), and the Japanese bridge at Giverny (1899-1900). Debussy exploited the same ideas in several ways. On the one hand, he rescored piano pieces for other instruments. In 1912, for example, he created a piano/violin version of the cakewalk “Minstrels” for Arthur Hartmann, a future member of the violin faculty at the Eastman School of Music. On the other hand, Debussy liked to make piano versions of orchestral scores: although he always intended to score Pelléas et Mélisande, he created a piano version to help the singers rehearse their parts and to make so much needed income.

But perhaps the most important way in which Debussy left his mark on later generations was by attacking the status quo: he took delight in shocking his peers as well as the Establishment. His role model in this regard was the American writer Edgar Allan Poe. Besides embracing the bohemian lifestyle, Poe is primarily remembered for cultivating the Gothic horror story, a genre that is specifically designed to shock audiences. His story “The Fall of the House of Usher” literally screams of the Gothic: an ancient building set in a distant locale, a cast of disturbed and disturbing characters, a family curse, a creepy vault beneath the building, and a terrifying storm scene. Poe’s snapshot of the house itself is particularly evocative: the main hall is flanked by Gothic archway, minute fungi cover the exterior walls, and a barely perceptible fissure zigzags down the walls.

Although Poe’s work was often ignored in America, it became popular in France during the 1850s and 1860s thanks largely to the efforts of Baudelaire. In fact, Baudelaire not only translated many of Poe’s stories into French, but he also wrote essays about Poe’s life and work. Baudelaire particularly admired Poe’s exquisite sense of literary form and his uncanny ability to expose the most sinister and paranoid aspects of the human psyche. Other Symbolist writers and painters followed Baudelaire’s lead. In 1875, Stéphane Mallarmé published a translation of Poe’s poem “The Raven” with illustrations Édouard Manet and in 1877 he wrote a homage entitled “Le Tombeau de Edgar Poe.” And through his close contacts with Baudelaire and Mallarmé, the Symbolist Villiers de l’Isle-Adam wrote a string of Gothic tales in the style of Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840).

Also under Poe’s spell was Villiers’ protégé Maurice Maeterlinck. Born in the Belgian city of Ghent and trained as a lawyer, Maeterlinck met Villiers during a visit to Paris in 1885 and Mallarmé when the latter came to Ghent in 1890. A couple of years later, Maeterlinck completed his remarkable play Pelléas et Mélisande. The story itself is a classic love triangle. Golaud, who is heir to the throne of Allemonde, marries Mélisande. She, however, is attracted to his younger half-brother Pelléas. Golaud is jealous and, out of desperation, kills them both. But the surroundings are quintessentially Gothic. Set in a remote Medieval castle, the drama unfolds against the same backdrop of death and decay as “Usher.” The kingdom of Allemonde is gripped in a deadly famine and the royal family has no empathy whatsoever for its subjects. Golaud is violent whenever he feels challenged: he threatens Pelléas, harasses his young son Yniold, and abuses Mélisande. The vault scene is particularly creepy and specifically recalls “Usher.” Maeterlinck even describes how the walls have tiny cracks and that might engulf the whole castle when people are unaware!

Poe’s Gothic tales likewise left an indelible mark on Debussy. In 1890, Debussy mentioned that he was working on a symphonic piece based on “Usher” and quoted the story in a letter a couple of years later: “Try as I may, I can’t regard the sadness of my existence with caustic detachment. Sometimes my days are dull, dark and soundless like those of a hero from Edgar Allan Poe!” Debussy became fascinated by Pelléas et Mélisande early in 1893, when he purchased a copy of the first edition and attended its premier. Although the play attracted him in many ways, Debussy was clearly drawn to its Gothic elements. He claimed that the vault scene is “full of impalpable terror and mysterious enough to make the most well-balanced listener giddy.” And he found Golaud’s interrogation of Yniold equally horrific: “It’s terrifying, the music’s got to be profound and absolutely accurate! There’s a ‘petit père’ that gives me nightmares.”

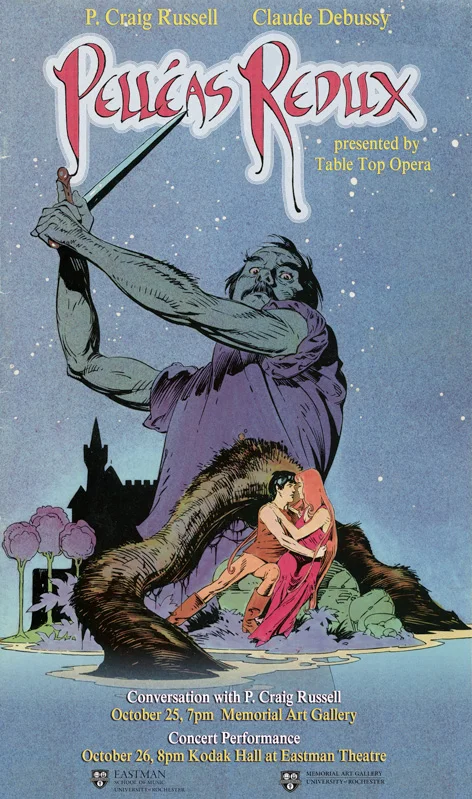

Pelléas Redux recaptures the shocking aspects of Pelléas et Mélisande. It takes Maeterlinck’s avant-garde ideas a step further by substituting traditional operatic sets with P. Craig Russell’s comic book version of the story and by replacing the singers and symphony orchestra with a contemporary ensemble comprised of classical, jazz, and electronic musicians. Russell’s illustrations are given in their entirety and, using various cinematic techniques, are presented in the form of a motion comic. Debussy’s original score is trimmed down to under two hours, the standard time frame for concert performances and is rescored for a chamber ensemble: violin, alto sax, trumpet, cello double bass, electric guitar, keyboards, and percussion. The performance will feature Charles Castleman (violin), Griffin Campbell (alto sax), Clay Jenkins (trumpet), Albert Kim (keyboard), Ken Lurie (cello), Dariusz Terefenko (piano), Jason Titus (electric guitar), James VanDemark (bass), Christopher Winders and Matthew Brown (sound and projections).